|

||||||||||||

Understanding concrete jointsWe use concrete joints in concrete flatwork (and indeed in concrete masonry and brickwork) for very good reasons. The correct placement of joints in concrete will maintain the appearance and long life of your slabs and pavements. The reason for joints is that concrete moves.

A good long lasting concrete job depends on many factors, and the correct planning, choice and positioning of the joints is a crucial part. But with the best joints in the world your concrete will still crack if you neglect the other important aspects like sub-grade preparation etc. etc. Concrete moves in two ways. 1.) Shrinkage from water loss. The three main constituents of concrete are aggregate, cement and water. When the water dries out the concrete shrinks. Not a large percentage in a well designed mix but all concrete when it dries shrinks. This shrinkage happens mostly in the time immediately after the concrete is poured, but it continues on in a slowly diminishing rate for years. It is common for shrinkage cracks to appear a long time after the event. The pressures in the concrete builds up until a crack appears. Our best hope is to keep shrinkage to a minimum, but knowing that it will occur we design control joints in concrete. The control joint is there for one reason only, to anticipate shrinkage and to provide a nice straight line for it to occur rather than the unsightly mess on the right. Other good concrete practices can minimise shrinkage, the correct placement of rebar and curing concrete correctly can reduce the shrinkage but it can never stop it entirely. 2.) Thermal Movement. The daily and seasonal cycles of warm and cold provides movement to all building materials. Hot material expands and then it contracts as it cools. I have a nice patio area with a corrugated iron roof. Quite often I am stirred out of a lunchtime nap by a series of loud cracks from the roof. It is the metal expanding against the grip of the screws. In the evening it shrinks to the same noises. In concrete this movement is very small. It is so small that we can't detect it with the naked eye, but concrete being what it is the force of even this small change in size can be extremely powerful and potentially destructive. The types of concrete joints.Because concrete moves in two ways, we similarly have two distinct types of concrete joints.

Every concrete joint is one or the other of these two types. Construction joints. Many large companies pour concrete in continuous pours, they work shifts and huge projects are completed without any stop. The rest of us like to get a bit of sleep and leisure now and again, so during the course of a job we halt construction and have a bit of a break. When we stop the work and then restart it we form construction joints between each days work. On a well planned job these construction joints may well occur at an expansion joint, but they can be made at a control joint also. One other joint that has a name but it should never happen. Cold Joints or unplanned concrete joints. Imagine this scenario, you are half way through a pour and the next truck is delayed, or the concrete pump breaks down. (been there, done that, more than once!) Concrete should be poured steadily from one end of the work to the other keeping the fluid edge. Always have a backup plan, do a "what if" check beforehand so that you won't be short of tools or materials in the event of something going wrong. Remember Murphy's Law.

Concrete joints - A short digression. The term expansion joint is often used under the mistaken impression that concrete once poured expands to larger than its original size. It never does this. Any thermal expansion is almost always less than the original shrinkage that happens to freshly poured concrete. In a perfect world once the concrete has dried out leaving shrinkage gaps between the reasonably spaced panels, then there would be no need for expansion joints.

Placement of concrete joints.

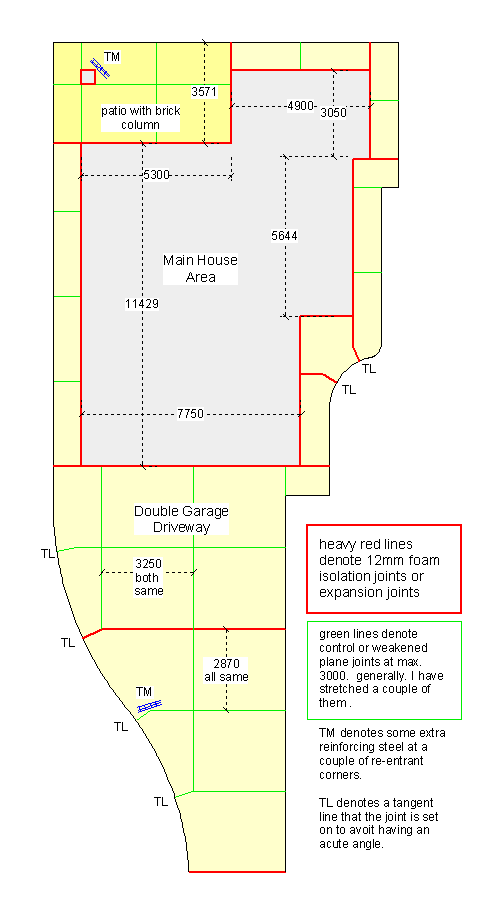

In the silly little plan above I have not tried to fit things in that would make it easy. I just sketched it out and then worked the joint lines out after, which is what the contractor has to do when faced with a weird plan. Some of the sizes go a touch over the recommended 3000, but in the end it is up to the individual. If you are trying to skimp on concrete depth or reo mesh maybe because you are mixing on site or you only have a lightish mesh available, then tighten up the joints. A tangent is a line that just touches an arc at one spot. The lines that I have drawn and denoted TL are square off them. As far as re-entrant corners go it it just about impossible to do a job like this without them. The problems always arise because of people being completely ignorant of what is going on. Now that you know about half the battle is won. Just be aware of them and do the best compromise that you can. I have put in a couple in the sketch. The "TM" refers to trench mesh, which is used in trenches for foundations and has in general larger bars closer together than standard fabric used on driveways. I have used it whenever it was handy, but don't go out an buy stuff specially. Any spare reo bars will do. The trick is to imagine two hands trying to pull the concrete apart at that spot and so just put in some rebar to stop them. An important point to note when planning a concrete pour to say a driveway slab is the use of a plastic sheet under the concrete.

Not found it yet? Try this FAST SITE SEARCH or the whole web |

Hire Equipment  Furniture Fittings - Architectural Hardware - Electronic Locking Systems - Technical Hardware BuilderBill sponsorship

When I were a lad we used to say "there's only two sorts of concrete. Concrete that's cracked and concrete that's gunna crack".

|

|||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Please Note! The information on this site is offered as a guide only! When we are talking about areas where building regulations or safety regulations could exist,the information here could be wrong for your area. It could be out of date! Regulations breed faster than rabbits! You must check your own local conditions. Copyright © Bill Bradley 2007-2012. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||